Yes, I’m writing about transport in London again, even though I live the best part of 200 miles away. This time, it’s about the ongoing efforts to get diesel trains out of the capital, and what progress is being made. I’m going to look at each of London’s rail termini in turn, and see what proportion of trains are running on electric power.

Background: London’s air quality problem

London, like many cities, has had an air quality problem for centuries. There was the Great Stink in 1858, the rise of pollution during the Industrial Revolution, and more recently, emissions from transport. Though I’ve never lived in London, I’ve made regular visits over the years, and still remember having black snot from the poor air quality.

The good news is that air quality in London is improving. Over the years, the Ultra-Low Emission Zone has expanded to cover just about all of London, and reduced the number of polluting vehicles on the road. Improving air quality has been a particular aim of mayor Sir Sadiq Khan, who has even written a book about it (sponsored link). It’s worth a read – it’s relatively short but gets the message across.

But the ULEZ is just about road transport. Today, I’m focussing on rail transport, and specifically looking at the twelve key London termini. Long-distance rail travel in Great Britain is generally focussed on London, and so if you get rid of diesel trains from London, you also get rid of them from other parts of the country too.

Cannon Street

Starting alphabetically, Cannon Street is the first terminus, and one that I personally have never been to. For many years, it was never open on Sundays, although it has operated seven days a week since 2015. All the trains to Cannon Street are operated by Southeastern, who only operate electric trains. So, Cannon Street is fully electrified – probably a good thing, as it’s an enclosed station with low ceilings.

Charing Cross

A little further west along the River Thames is Charing Cross. Like Cannon Street, it too has low ceilings due to over-site development, and is also only served by Southeastern. So, no dirty diesel trains here either.

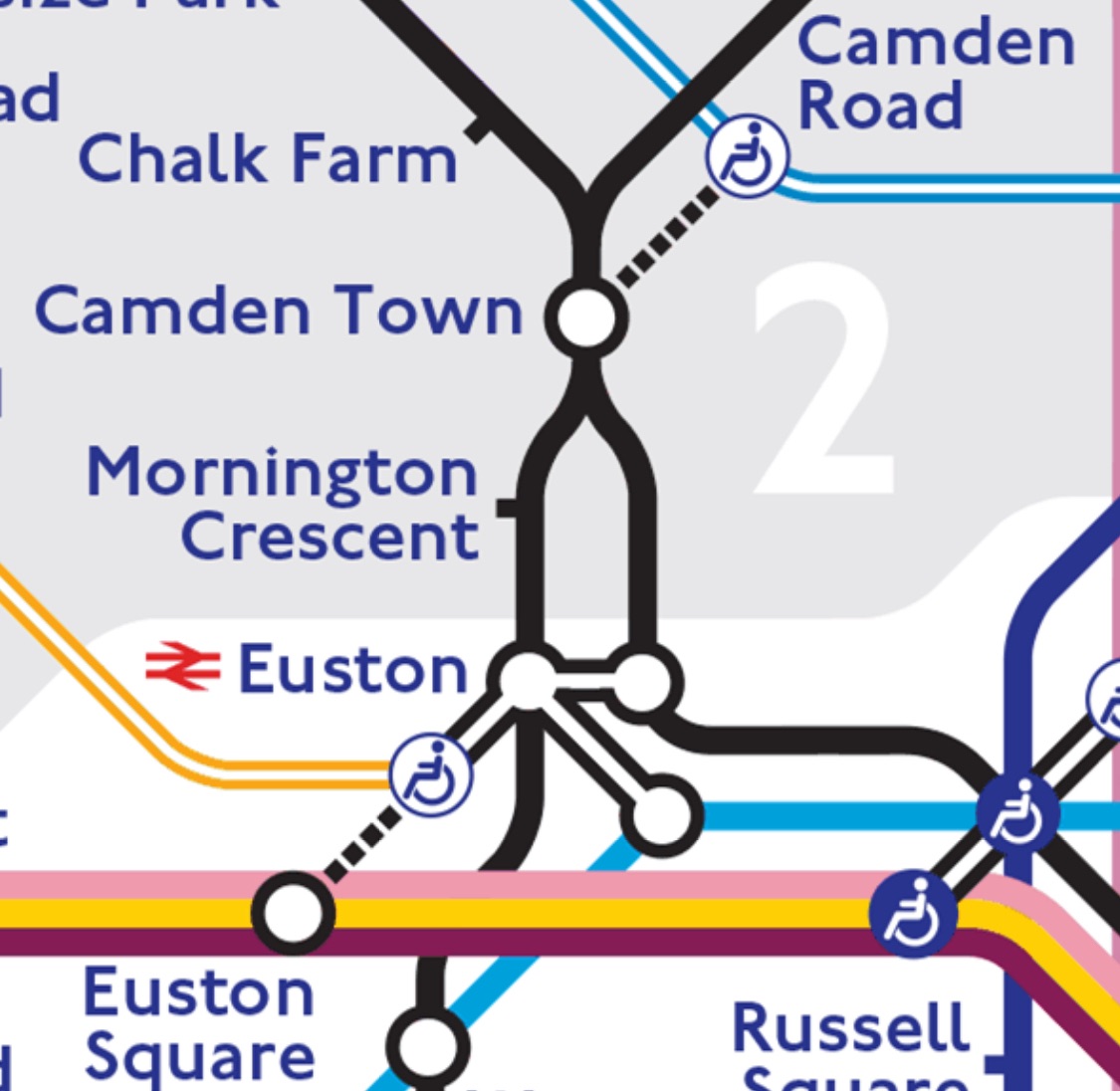

Euston

Euston was controversially rebuilt in the 1960s as part of the then British Rail’s upgrade of the West Coast Main Line. This included electrification, and so nowadays almost all of the trains which operate from Euston are electric. Avanti West Coast operated a few diesel services to Chester and onwards to North Wales, but are being replaced with new Hitachi bi-mode trains that can operate on electric power as far as Crewe in Cheshire.

There may be some diesel visitors to Euston on occasion, as services that would normally call at Paddington are diverted to Euston during construction work at Old Oak Common. This includes the Night Riveria Sleeper, and some of GWR’s Hitachi bi-mode trains that may have to run on diesel power as they navigate through their diversionary routes.

Fenchurch Street

Fenchurch Street is the smallest of London’s rail termini, with just four platforms. It’s another one that I’ve never been to, as I’ve never needed to go to places like Tilbury or Southend. If I did, I would be able to catch an electric train there courtesy of c2c, whose entire fleet is electric. Indeed, the lines out of Fenchurch Street were some of the first to be electrified using overhead cables in the late 1950s.

King’s Cross

Being from Yorkshire, King’s Cross is the London terminal I’m most familiar with. Most (but not all) of my rail journeys to and from London include King’s Cross.

Though overhead electric wires were strung up for commuter services in the 1970s, the wires didn’t go north of Peterborough until the 1990s. Even then, British Rail still operated a mixture of electric and diesel trains (the venerable High Speed Train) and this persisted until very recently. Their replacement came in the form of more of Hitachi’s bi-mode trains, introduced by LNER. Such trains are also operated by open access operators Hull Trains and Lumo (although Lumo’s trains are all electric).

The outlier is another open access operator, Grand Central. Whilst they operate a small fraction of the services from King’s Cross, at present, they’re all still diesel-powered. That’s due to change, once again thanks to Hitachi who are building some tri-mode trains that can run on electric wires, batteries and diesel. The order for these was only announced a few weeks ago, so it’ll be 2-4 years before we see the back of the last purely diesel trains from King’s Cross, but there’s good progress being made.

Liverpool Street

I’ve only ever been to Liverpool Street mainline station once, which was to use the Stansted Express back in 2009. That was, and still is, an electric train, and indeed all the trains that operate from Liverpool Street are electric. Well, almost: Greater Anglia has a small fleet of bi-mode trains, which for once are not made by Hitachi but by Stadler. Occasionally these run to Liverpool Street, although their main stomping grounds are across Norfolk and Suffolk running regional services. In any case, they should run on electric power when available, so we can tick off Liverpool Street as being electric.

London Bridge

London Bridge underwent a stunning rebuild in the 2010s. I used the old station a bit pre-rebuild and it was awful – the new station is much better.

In the 1930s, the then Southern Railway invested in extensive electrification of its lines, using the third rail principle. Instead of overhead wires, a third metal rail is added to the outside of the two running rails and trains pick up power that way. As such, almost all of the railways in the south-east of England are electrified. Indeed, many have never routinely hosted diesel trains, having gone straight from steam to electric.

However, a handful of lines didn’t get electrified, including services to Uckfield along the Oxted Line. Therefore, there’s a small fleet of diesel trains that serve London Bridge.

Marylebone

Oh dear.

We were doing so well, weren’t we? Seven stations in, and all were either completely electrified, getting there, or had just a handful of diesel services. And then Marylebone has to ruin everything for us.

Okay, so Marylebone is quite a nice London terminus. Whilst not as small as Fenchurch Street, it’s still quite dinky and less overwhelming than some others. It survived closure in the 1980s, and Chiltern Railways has been one of rail privatisation’s few success stories, with new services, new stations and improvements to infrastructure. Indeed, if you want to get a train between London and Birmingham, and don’t mind it being a bit slower, it’s much nicer going from Marylebone to Birmingham Moor Street.

But Marylebone isn’t electrified – at all. Every service that terminates there is a diesel train. And it shows – the last time I was there, there were advertising boards proudly telling us that they had air purification technology built into them. But this wouldn’t be necessary, if the trains that were calling there didn’t spout diesel fumes.

There have been some lacklustre efforts to improve the situation – one of Chiltern Railways’ trains was modified to be a diesel-battery hybrid, and it could use its battery at low speed and in stations. Alas, this was never rolled out to other trains in the fleet. Also, the oldest of Chilterns’ trains are now around 30 years old and need replacing, so putting up electric wires would be timely to prevent a new order of diesel trains.

One issue is that trains from Marylebone to Aylesbury share track with London Underground’s Metropolitan Line services (a relic from when the Metropolitan Line went all the way to Aylesbury). These lines are owned by Transport for London, and electrified using a unique four-rail system. Any electrification scheme would need to take this into account, especially as TfL probably won’t want overhead wires stringing up over their infrastructure. Dual-voltage trains, which can run on both overhead and third-rail electrified lines, are a thing and are used daily on Thameslink services, for example, but this would need careful planning to work out.

Moorgate

Moorgate is a London terminus, albeit of just one line nowadays – the Northern City Line. Historically, this line was considered part of London Underground and was grouped with the Northern Line, and so it’s electrified.

Until the 2010s, some Thameslink services terminated here too, but these were axed to allow platform extensions at Farringdon station. They too were electric though.

Paddington

Paddington was a latecomer to the electrification party (which sounds like a round from I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Clue). The first electric trains started in the late 1990s, and even then, it was just the new Heathrow Express service. However, the announcement of the Great Western Main Line Electrification project allowed it to catch up, with electric wires extended all the way from Airport Junction in West London across the Welsh border into Cardiff. However, that project also went massively over budget, and as such, lines to Bristol and Oxford never received their wires.

Whilst some electric trains run from Paddington, the majority are those Hitachi bi-modes again, which can run on electric power where available and switch to diesel if needed. This has meant that Paddington has moved from having only a handful of electric trains in the 2000s, to being almost entirely electric now. There’s just a handful of commuter trains at peak times that use diesel Networker Turbo units, and the Night Riveria Sleeper train, which uses diesel locomotives. Perhaps, in future, the Night Riveria will be hauled by bi-mode locomotives, such as the new Class 93 and Class 99 locomotives under construction.

See Marylebone? It can be done.

St Pancras

The rebuild of St Pancras for High Speed One services was excellent. I have vague memories of the tired old station, and now it’s much better.

However, there are still a few diesel trains plying their trade at St Pancras. These are the trains which take the Midland Main Line up to Sheffield and Nottingham. This line should have been electrified in its entirety by now; instead, it’s being done on a piecemeal basis and currently the wires are projected to stop just south of Leicester.

The good news is that new trains are on order – and yes, they’re yet more bi-mode trains from Hitachi, although they’ll be slightly different than the units used by other operators. And East Midlands Railway has introduced electric trains from Corby into St Pancras – impressive as Corby station only re-opened in 2009.

Victoria

Victoria is big and confusing. I’ve used it a few times and can’t say I’m a fan. But all the trains that run from Victoria are electric, so that’s good.

Waterloo

Until the Elizabeth Line came along, Waterloo, with its 24 platforms, was the busiest station in the UK. Now it’s third, but still very busy.

It’s also a bit like London Bridge, in that the vast majority of trains are electric, but a handful of diesel services limp on to serve places beyond the reach of the third rail network. Doing something about these services is more pressing than those from London Bridge to Uckfield, as the trains are older and due for replacement. Various ideas have been floated around, but it seems probable that we’ll see existing electric trains getting batteries bolted onto them, and some discontinuous electrification to charge them up. That could be some of the new Class 701s, which have had one of the most protracted entries into service of any new train, or some Class 350s which are about to go off-lease from London Northwestern.

Conclusion

Overall, the majority of train services into London are already electric, including all services to seven of the twelve stations. Of the remaining five, diesel trains make up a small number of services at three of them, and we’ll likely see the back of the last remaining diesel trains at King’s Cross and St Pancras by the end of the decade. The lack of any sort of electrification at Marylebone is a bigger problem to tackle, but then Paddington has gone from being all diesel to almost all electric within 30 years; indeed much of that progress has been within the last 10-15 years. It’s also clear that bi-mode trains have a future until further electrification outside the capital takes place.