Today I’m written about ‘hidden’ motorway service stations. These are places which offer most, if not all of the facilities of standard motorway services, but they’re typically not signposted from the road.

M1 – Markham Vale Services

There’s one that we’ve used a couple of times at Markham Vale on the M1 – most recently on our way back from Hardwick Hall earlier this month. Like the other hidden motorway services that I’ll mention here, this is built at an existing junction, in this case Junction 29A. As you may gather from the ‘A’ in the junction number, this isn’t one of the original M1 junctions. It was added in the 2000s to improve access to the Markham Vale Employment Growth Zone, and so the area is mostly offices and warehouses.

But a strip of land next to the motorway is now home to Markham Vale services. Unlike typical motorway service stations, there isn’t one single amenity building. Instead, it’s a cluster of separate buildings with their own car parks. There’s a fuel station, a small Asda, a Starbucks, a KFC, a McDonalds, a local fish and chip shop and a pub. Of these food outlets, all of them (except the pub) offer drive-through service as well. I’m not sure a drive-through pub would be a good idea. Most of these are operated by EG (formerly Eurogarages).

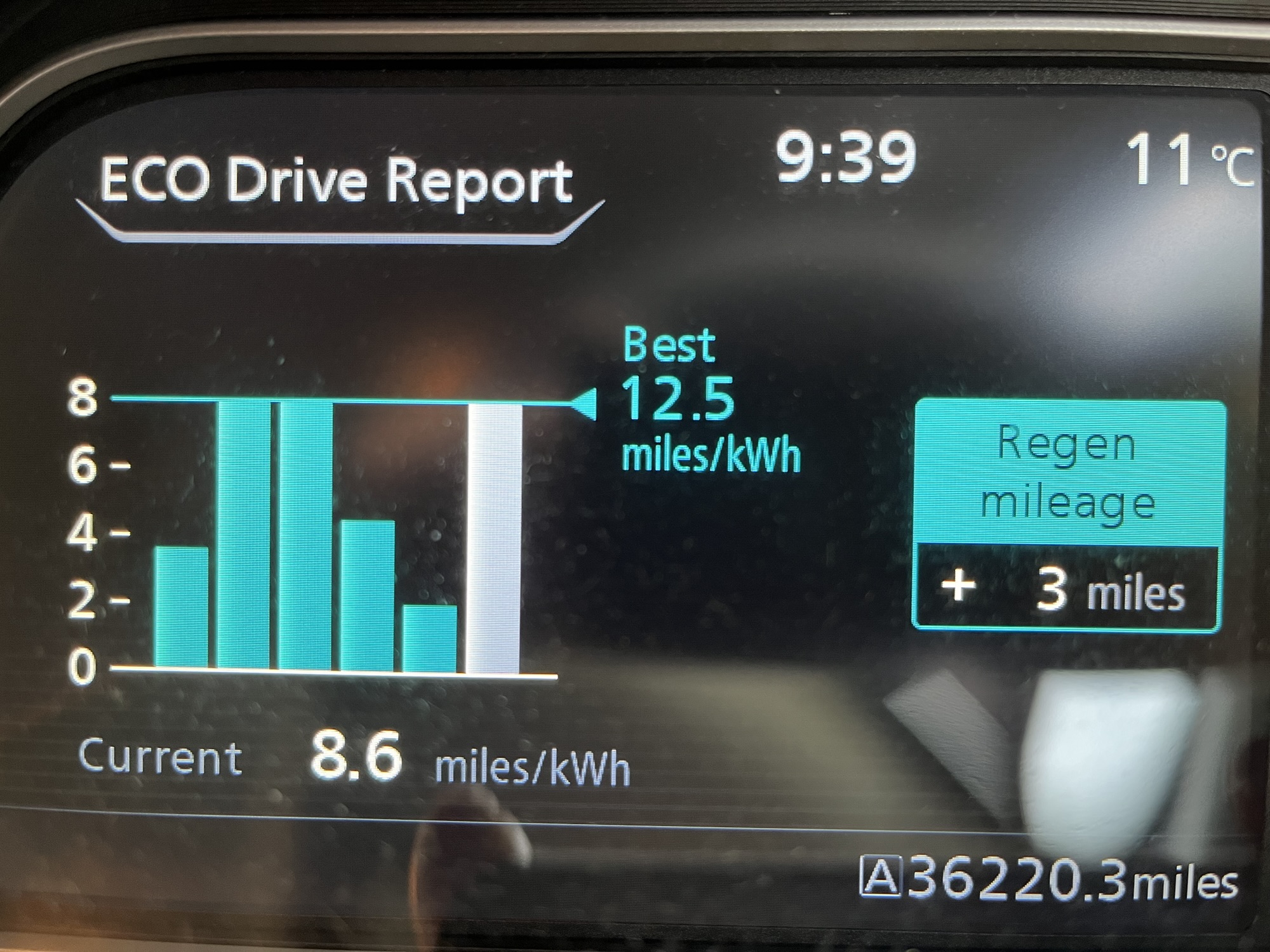

For electric vehicle owners, there are three separate sets of chargers, on the EV Point, Osprey and Instavolt networks, and they all happen to charge slightly different prices. When we were there, EV Point was cheaper, by 10p per kWh, than the others. Across the road, Gridserve are building one of their ‘electric forecourts’ which may open soon as well. That’ll offer 25 rapid chargers and its own amenities, as well as a children’s playground.

Because there’s not one central building, and because it’s not signposted, it’s a bit quieter than others. We were there on a Saturday afternoon and it was moderately peaceful. If you’re sensitive to noise and don’t like big echo-y spaces, then somewhere like this may be preferable.

There used to be a huge totem sign next to the fuel station that was viewable from the M1, but this seems to have been removed in recent years.

M62 – Plantation services at Gildersome

A little closer to home is at Gildersome interchange, or Junction 27 of the M62. It’s where the M621 splits off towards Leeds, and, to the south, is home to Birstall retail park and Ikea.

But to the north of the junction, just off the A650, is another EG site, which calls itself ‘Plantation Services’. Again, there’s a fuel station with a small supermarket – currently Spar, but EG is under the same ownership as Asda, so it could change. There’s also a Greggs, a Subway, a Starbucks and a Popeyes Chicken.

For electric vehicles, there are several chargers on the EV On The Move network.

It’s a compact site, but it’s easy to get back onto the M62 (or M621) after using it.

M62 – Chain Bar services

Going back a junction, to junction 26, there’s also a smaller hidden service station here as well. Junction 26 is where the M606 heads off towards Bradford, but there’s also a massive roundabout here too.

Just off this roundabout, on the A58, is a small site with a Starbucks, a Greggs and a Subway. There isn’t anywhere to get fuel here, but there are rapid chargers, again on the EV On The Move network. It therefore won’t surprise you to learn that this is also an EG site, who call it ‘Cleckheaton Services’.

Separately, but a little further down the road, is a pub with more rapid chargers (Osprey network), and across the road is a Premier Inn and another pub.

A1 (M) – Coneygarth services

This is a bit of a cheeky one. Coneygarth services is located at Junction 51, which is also the nearest junction to Leeming Bar Rest Area. However, whilst Leeming Bar is officially signposted from the motorway, Coneygarth is merely marked out as a ‘truck stop’. That doesn’t mean that it’s restricted to trucks though – cars can use it as well, and there’s fuel, car chargers, a Londis shop and a Subway available.

Here’s why it’s cheeky. The ‘rest area’ at Leeming Bar pre-dates this section of the A1 being converted to motorway in the 2010s. As motorway junctions are more spaced out, traffic heading to Leeming Bar rest area has to leave at junction 51 and then travel around a mile along an access road. Coneygarth services was then established at the junction, and so you could just call here, rather than take a longer detour to Leeming Bar.

Also, Leeming Bar is generally regarded as being the worst in the UK. The fact that it is considered a ‘rest area’ rather than a full services should be a clue; we had the misfortune of calling there on a baking hot afternoon in 2024. There’s literally just a Costa, a hidden-away McDonald’s, a fuel station and some car chargers. The main amenity building, which once hosted a hotel, is derelict, and has been for some time.

Advantages of ‘hidden’ motorway services

I’ve just listed three examples that I’m aware of, but there will undoubtedly be others. Indeed, as building a few electric vehicle chargers is much easier than a whole fuel station, I imagine we’ll see more of these pop up alongside motorway junctions where the land is available.

Because they’re not signposted from the motorways themselves, they tend to be quieter. This is especially true of those that you can’t see whilst driving, as you need to know that they’re there. That may also mean that the fuel is cheaper, and that you can charge your electric car more cheaply too.

You may also find a different range of food options available. If you’re planning a longer stop, you could have a nice pub lunch at Markham Vale. Very few ‘official’ motorway services have pubs – Beaconsfield services on the M40 had a Wetherspoons until 2022. Of course, you absolutely should never drink and drive.

I suppose the disadvantages are a narrower range of shops or food outlets, and that they’re more spread out. Not so good if it’s raining.