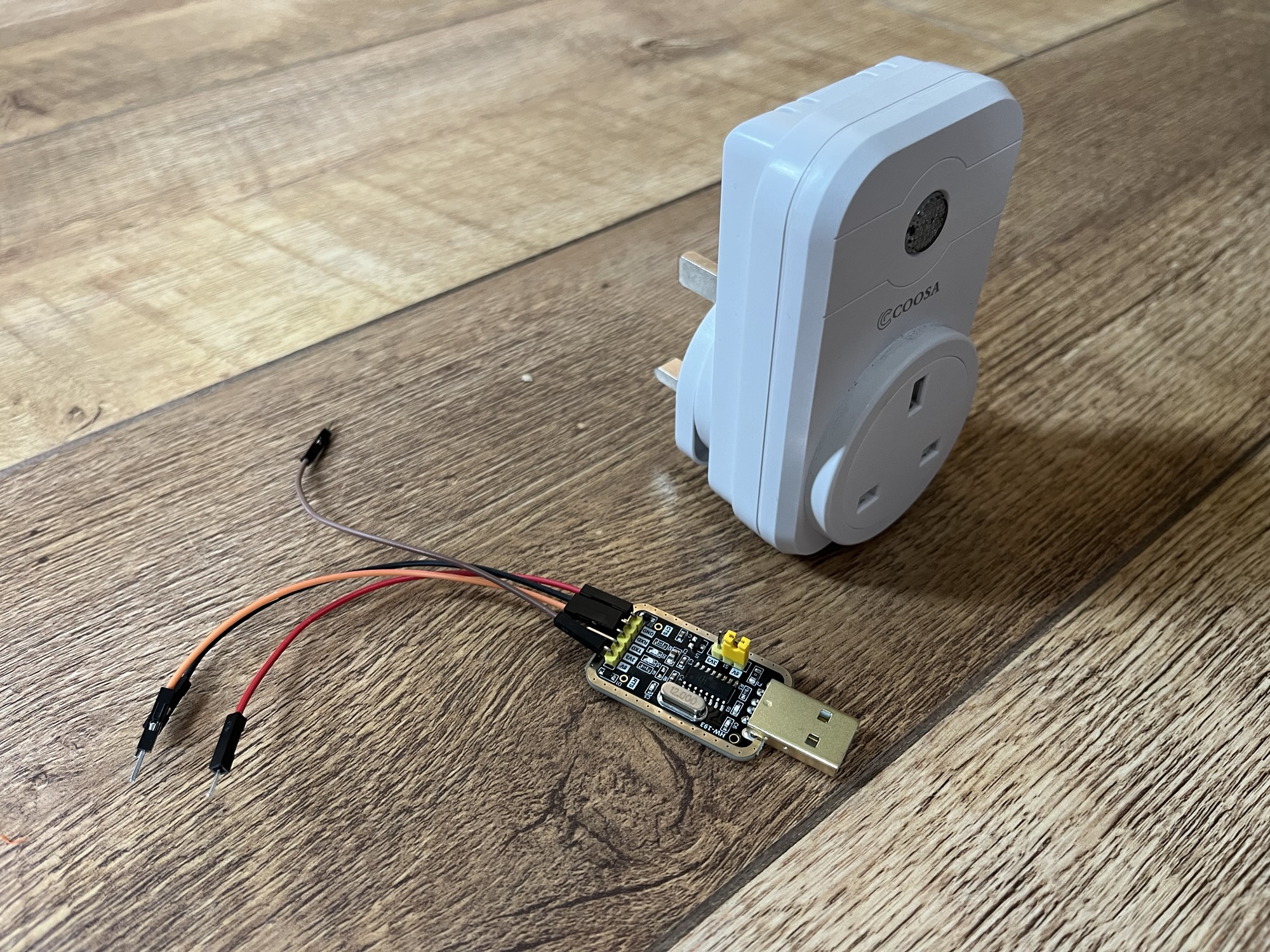

Back in June, I flashed some old Tuya Wi-Fi smart plugs with Tasmota firmware. I’ve now re-flashed one of them with ESPHome, an alternative firmware by the Open Home Foundation who are the same people as Home Assistant. In this blog post, I’m going to outline:

- Why the change from Tasmota to ESPHome

- How to build a YAML file for ESPHome

- The flashing process

This is a longer blog post, so if you want to skip the explanations for each section of the YAML file and just want to go ahead and do this yourself, you can download my pre-made YAML file from GitHub, and then follow these instructions.

Why the change from Tasmota to ESPHome

If you’re starting out with custom firmware for your existing devices, then I would still recommend Tasmota. It’s much easier to set up, as you install it first, and then configure it. There’s also a much more extensive repository of supported devices, so you shouldn’t need to do much manual tinkering once Tasmota is installed.

ESPHome, by contrast, requires you to configure it first, and then install it. Furthermore, rather than offering a web interface for configuring your devices, instead you have to do this in a YAML file. And then you have to compile the firmware specifically for your device and upload it.

That being said, ESPHome is much more powerful. You can build automations into it that run on the device itself, rather than through, say, Home Assistant. And as each firmware binary is compiled for each device, it’s much smaller, which allows for easier updates. On some Tasmota devices, you have to install a ‘minimal’ version of the firmware before you can upgrade. By contrast, with ESPHome, your device should be able to update directly to new firmware versions.

As you would expect, ESPHome integrates better with Home Assistant. Indeed, one reason for me changing to ESPHome is that the Tasmota integration takes a while to start up and is one of those slowing Home Assistant down. Firmware updates are also offered through Home Assistant, so you don’t need something like TasmoAdmin to manage firmware updates for multiple Tasmota devices.

Building the YAML file

I’m going to go through each section of the YAML file, to explain what it does, and why it’s necessary. Some of these are specific to the plugs that I’m using, and may not transfer to other devices.

Firstly, with Tasmota still running, open the Configuration screen and choose Template. This will give you a list of the GPIO pins, and what they currently do in Tasmota. You’ll need to note these, so that you can tell ESPHome what pins to use. On mine, these were the ones in use:

- GPIO4 – LED

- GPIO5 – Relay

- GPIO13 – Button

The LED is the light on the smart plug, the relay is what controls whether the power is on or not, and the button is the physical button on the smart plug that controls the relay. Whilst the relay is the most important, to preserve the device’s full functionality, we need to tell ESPHome about all of them.

The ESPHome section

Here’s the first bit of the YAML file:

esphome:

name: $name

friendly_name: $friendly_name

esp8266:

board: esp01_1mIf you use the wizard in the ESPHome Device Builder, then these will have been created for you and filled out with whatever name you’ve chosen. The second block tells ESPHome that the device has an ESP8266 chip, and it’s a generic board. This was the default selection and seemed to work fine for me.

Logging, API, OTA, Wi-Fi

Next, we have the following:

# Enable logging

logger:

# Enable Home Assistant API

api:

encryption:

key: $key

ota:

- platform: esphome

password: $password

wifi:

ssid: !secret wifi_ssid

password: !secret wifi_password

# Enable fallback hotspot (captive portal) in case wifi connection fails

ap:

ssid: "esphome-smartplug"

password: $fallbackpassword

captive_portal:The logger means that the device will keep logs. It’s up to you whether you keep this in, but as I was coming up with this myself, I decided it would be best to help debugging.

Because I’ll be using this smart plug with Home Assistant, we need to include the ‘api:‘ section. Again, the ESPHome device builder should have filled out an API key here.

The ‘ota:‘ section allows for ‘over the air’ updates. This means that your device can update to new versions of ESPHome without needing to be plugged in to a device, either over USB or a UART connection.

In the ‘wifi:‘ section, this includes references to the ESPHome Device Builder’s secrets file which should have your Wi-Fi network SSID and password. If the smart plug can’t connect using these details, then, as a fallback, it’ll create its own access point. This is where we also need the ‘captive_portal:‘ section, which allows the user to select a Wi-fi network if the one we’ve pre-programmed can’t be found.

Web server

Next, we have this section:

web_server:

port: 80This is optional, but it creates a Tasmota-like web app that you can connect to. This will allow you to press the button on the smart plug, view the logs, and upload firmware. We don’t need it, but it partially replicates the functionality of the previous Tasmota firmware, and helps with debugging.

Binary sensor

This is the section that enables the hardware button on the smart plug to work:

binary_sensor:

- platform: gpio

pin:

number: GPIO13

mode: INPUT_PULLUP

inverted: True

use_interrupt: True

name: "Power Button"

id: "smartplug_button"

on_press:

- switch.toggle: "smartplug_relay"

disabled_by_default: TrueWe’re telling ESPHome that the button is attached to GPIO pin 13, and, when the button is pressed, to toggle the relay on or off. I’ve also added the ‘disabled_by_default: True‘ line so that it doesn’t show in Home Assistant.

Switch

Now, we need to configure the relay, and make it available to Home Assistant:

switch:

- platform: gpio

name: "Switch"

id: "smartplug_relay"

pin: GPIO5

on_turn_on:

- output.turn_on: led

on_turn_off:

- output.turn_off: led

restore_mode: RESTORE_DEFAULT_ONSo, we’re telling Home Assistant that the relay is connected to GPIO pin 5. We’re also telling it to turn on the LED when the relay is turned on, and off again when it’s turned off. The ‘restore_mode: RESTORE_DEFAULT_ON‘ tells ESPHome what to do when the device boots up, perhaps after a power cut. I’ve set it to try to restore the status that it had before, but if it can’t, to turn the relay on.

LED

Here’s our final block, to tell ESPHome that there’s an LED

output:

- platform: gpio

pin: GPIO4

inverted: true

id: ledAgain, we tell ESPHome that it’s connected to GPIO pin 4. The YAML code in the Switch section tells ESPHome when to turn the LED on or off.

So, now we have a YAML configuration file. This should be added as a new device in the ESPHome Device Builder.

The flashing process

The good news is that switching from Tasmota to ESPHome is easier than from the original Tuya firmware. You probably won’t have to get out a UART converter and cables, unless you accidentally brick your device. Instead, you just need to follow these instructions, which involve manually downloading the firmware binary, and then uploading it to Tasmota. When the device restarts, it’ll be running ESPHome instead.