If you’ve upgraded to last month’s release of ESPHome 2025.11, you may start seeing this warning message about WPA when validating your YAML scripts, or compiling new versions:

WARNING The minimum WiFi authentication mode (wifi -> min_auth_mode) is not set. This controls the weakest encryption your device will accept when connecting to WiFi. Currently defaults to WPA (less secure), but will change to WPA2 (more secure) in 2026.6.0. WPA uses TKIP encryption which has known security vulnerabilities and should be avoided. WPA2 uses AES encryption which is significantly more secure. To silence this warning, explicitly set min_auth_mode under ‘wifi:’. If your router supports WPA2 or WPA3, set ‘min_auth_mode: WPA2’. If your router only supports WPA, set ‘min_auth_mode: WPA’.

The warning message is pretty self-explanatory, but it concerns upcoming changes to Wi-Fi Protected Access (WPA) in ESPHome that are due to be introduced in June next year.

A bit of a history of WPA

Honestly, if you’re using ESPHome, you’re probably sufficiently tech-savvy to know what WPA is, but if this blog post is less than 300 words, it’ll probably be largely ignored by search engines. So, you can skip this bit if you like.

WPA is what makes a secured Wi-Fi network secure. The ‘Wi-Fi password’ you put in when connecting to secure Wi-Fi networks is the WPA security key. It replaced Wired Equivalent Privacy, dating from the earliest days of Wi-Fi, which is so weak that you can probably crack it with a standard laptop nowadays in a few minutes. It used 64 or 128-bit RC4 keys.

There are three versions of WPA:

- The original version, which uses 128-bit keys with TKIP

- WPA2, which replaces TKIP with the more secure AES

- WPA3, the newest version, which improves the security of the key exchange and mitigates against easily guessable Wi-Fi passwords

Many devices that were originally designed to only support WEP could be upgraded to support WPA through software. At the time, this was a good thing – plain vanilla WPA was (and is) more secure than WEP. But as more security research has taken place, and computers have become more powerful, WPA is now also no longer recommended. WPA2 was ratified over 20 years ago, and so there are very few devices still in use that don’t support it. WPA3, meanwhile, is still quite new, having been ratified in 2018.

ESP devices and WPA

So, to bring this back to ESP devices and ESPHome in particular. At the moment, ESPHome defaults to the following WPA versions:

- Original, plain vanilla WPA on ESP8266 chips

- WPA2 on ESP32 chips

Remember, ESP32 is newer than ESP8266, despite the numbers. ESPHome has long supported YAML variables, that over-ride these defaults, to specify a specific WPA version to use when compiling.

What has changed with ESPHome 2025.11 is that, where you don’t specify the WPA version, you’ll see the above error when validating or compiling ESPHome for ESP8266 devices. Remember, these default to standard WPA at present.

Next June, when ESPHome 2026.06 is due for release, support for WPA will be dropped. So, if you don’t specify the WPA version, then from around June 2026, your ESP8266 devices will start using WPA2 the next time you re-compile them. This shouldn’t cause any issues, unless your Wi-Fi router is really old and doesn’t support WPA2. To which, I would say that replacing your router should be your priority, rather than amending your ESPHome configurations.

As for WPA3, this is only supported by the newer ESP32 family of chips. That means that, from June 2026, WPA2 will be the only option for ESP8266 chips.

How you can make the WPA warning go away

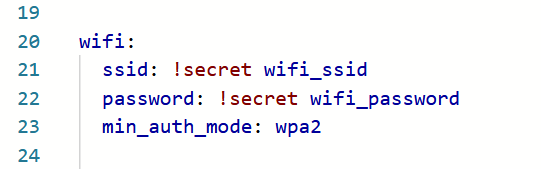

If you want, you can edit your YAML configuration files for your ESPHome devices to specify the WPA version to use. In the ‘wifi:‘ block, add ‘min_auth_mode: WPA2‘ underneath the network name and key, as so:

wifi:

ssid: !secret wifi_ssid

password: !secret wifi_password

min_auth_mode: WPA2That will ensure that ESPHome always uses WPA2 on your devices, and will hide the warning. If your devices have ESP32 chips, and your router supports WPA3, you can add ‘min_auth_mode: WPA3‘ instead; this will offer better security. For more information, see the guide to the ESPHome Wi-Fi component.

Will ESPHome eventually phase out WPA2 support as well? Perhaps, but WPA3 is still pretty new – if your router is more than five years old then it may not support it. Maybe it will in another 15 years or so.