Being able to access your Home Assistant instance outside of your home is useful, and there are many ways to do it – I’ve used several, including SWAG, an nginx proxy and more recently Nginx Proxy Manager. Today, I’m reviewing Homeway, a third-party service.

Setting up Homeway

Of all of the ways that you can enable remote access to Home Assistant, Homeway is one of the easiest. You sign up for an account on the Homeway web site, install an addon on your Home Assistant instance, and then you should be ready to go. Setting up the Home Assistant Companion App for iOS and Android is also supported, albeit with a little more work. If you don’t run Home Assistant OS or Supervised, and can’t install addons, then there’s also a Docker image or CLI client you can install.

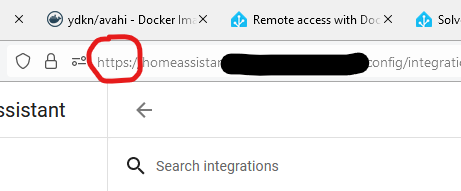

Once up and running, it works well – you log in first to Homeway, and then into your local Home Assistant instance. It’s all done over SSL, without needing to set up DNS, port forwarding or reverse proxies.

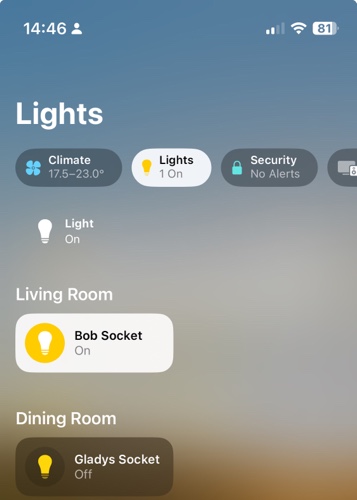

Homeway also supports easy integration with Google Assistant and Amazon Alexa. Having done it myself, setting up Google Assistant manually is a chore, and even when it’s up and running, I found it slow and unreliable. Using Google Assistant this way is much easier, as you don’t need to create a developer account. I also found it to be much faster, and I haven’t had any issues with devices showing as offline.

If you want to use Home Assistant’s voice control feature, then Homeway also provides access to an AI large language model for processing commands. Its chatbot is called Sage, and behind the scenes it uses ChatGPT 4 and Anthropic’s Claude services. For speech-to-text, it can also call on Google Gemini and DeepSeek R1, and there’s a choice of 25 voices from the various services it uses. As I use Google Assistant, I haven’t set this up myself.

What about Home Assistant Cloud?

What Homeway offers is very similar to Home Assistant Cloud. Home Assistant Cloud is provided by Nabu Casa, who employ many of Home Assistant’s developers and support the Open Home Foundation. So why should one use Homeway instead of Home Assistant Cloud?

The answer is price. I’ve compared the prices in a table:

| Monthly price | Annual price | |

| Home Assistant Cloud | £6.50 | £65 |

| Homeway | £3.49 | £29.88 |

As you can see, Homeway is less than half the price of Nabu Casa’s Home Assistant Cloud. And, it should be noted that Homeway offers a free tier, if you just want remote access, albeit with data limits. You only need to pay for heavy usage and Google Assistant/Alexa access. There isn’t a free or lower-priced tier for Home Assistant Cloud.

That being said, as of January, Home Assistant Cloud now includes backup storage as well, which Homeway doesn’t currently offer. It’s also worth reiterating that some of the money from Home Assistant Cloud subscriptions goes to paying staff to work on Home Assistant development. As such, Homeway is a little controversial, and I noted that the Home Assistant Community on Reddit seems to block the word ‘homeway’ from posts.

For me, the best feature about Homeway is the Google Assistant support, which works well. I already have good remote access set up using Nginx Proxy Manager and will continue to use this.