This is the second of two blog posts about the new London tube map, which saw the six lines that make up the London Overground gain their own identities. The previous blog post was about the ambiguous nature of the Waterloo & City Line’s step-free access. Meanwhile, today, I’m wondering whether some lines that make up London Underground could be given their own identities, like the Overground.

Some lines on the London Underground are simple through routes, with no branches – namely, the Jubilee, Victoria and Bakerloo Lines. For others, it gets a bit more complicated, and so this is a discussion of splitting some lines up, and giving them their own identity. None of these ideas are new – they’ve been talked about for years and exist in some official Transport for London plans – but it’s an opportunity to think of some names for them.

A history of splitting Underground lines

If you look at one of Harry Beck‘s tube maps from the 1930s, broadly speaking, you’ll be able to compare it easily to a modern day tube map – certainly when looking inside the Circle Line. The Victoria, Jubilee and Elizabeth Lines aren’t there, but otherwise, not a lot has changed in 90-odd years.

What you will notice, however, is the Metropolitan Line has lots more branches than it does now. Over time, however, the Metropolitan Line has been split up; firstly, the branch to Stanmore became a branch of the Bakerloo line, and is now part of the modern-day Jubilee Line. Then, in 1990, the line from Hammersmith to Barking was given its own identity as the Hammersmith & City Line, and the isolated East London branch became the East London Line. Incidentally, the East London Line is now part of London Overground, and recently gained its new identity as the Windrush Line.

I mention this because branches of tube lines have been given their own identities before, and so there is precedent for doing this.

The Wimbleware Line

Oh where is the Wimbleware? It’s a colloquial name for a service on the District Line, where trains run from Wimbledon in the south, to Edgware Road in the north. Wimbleware is a portmanteau of Wimbledon and Edgware, a bit like how the Bakerloo Line is a portmanteau of Baker Street and Waterloo, and indeed a contraction of its old name, the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway.

Operationally, the Wimbleware has always been somewhat separate from the rest of the District Line. Whilst nowadays, all District Line services operate using S Stock trains, it used to be that Wimbleware services used a different type of rolling stock to the rest of the line. Most District Line services used D78 stock (some of which is enjoying a new life as Class 230 and Class 484 trains on the main line), whilst Wimbleware services used C stock trains, more commonly found on the Circle Line.

Taking the Wimbleware out of the District Line, and giving it a distinct identity, would significantly simplify how the District Line appears. Right now, you essentially have two eastern branches, to Edgware Road and Upminster, and four branches to the west – to Ealing Broadway, Richmond, Wimbledon, and very occasionally Kensington (Olympia). The Wimbleware would just operate Wimbledon to Edgware services, leaving one eastern branch and essentially just two western branches.

But what will we call it?

I doubt we’ll see the name ‘Wimbleware’ on any tube maps in the future. It’s a nice colloquial name, but we also know that several lines of the London Overground had colloquial names that weren’t used. The Overground line from Gospel Oak to Barking was known as ‘The Goblin’, but its new official name is the Suffragette Line, and the Watford DC Line between Watford Junction and Euston has become the Lioness Line.

My suggestion would be the ‘Carnival Line‘ as it passes through Notting Hill, home of the annual Notting Hill Carnival. As with the new names of the Overground lines, like the aforementioned Windrush line, it highlights and celebrates London’s diverse culture, as well as giving a really obvious suggestion of which line to take if travelling to the carnival.

Alternatively, if permission could be obtained from the estate of Elizabeth Beresford, how about the Womble Line? It would celebrate the famous fictitious residents of Wimbledon Common, who look after the environment by reusing people’s rubbish.

Splitting the Northern Line

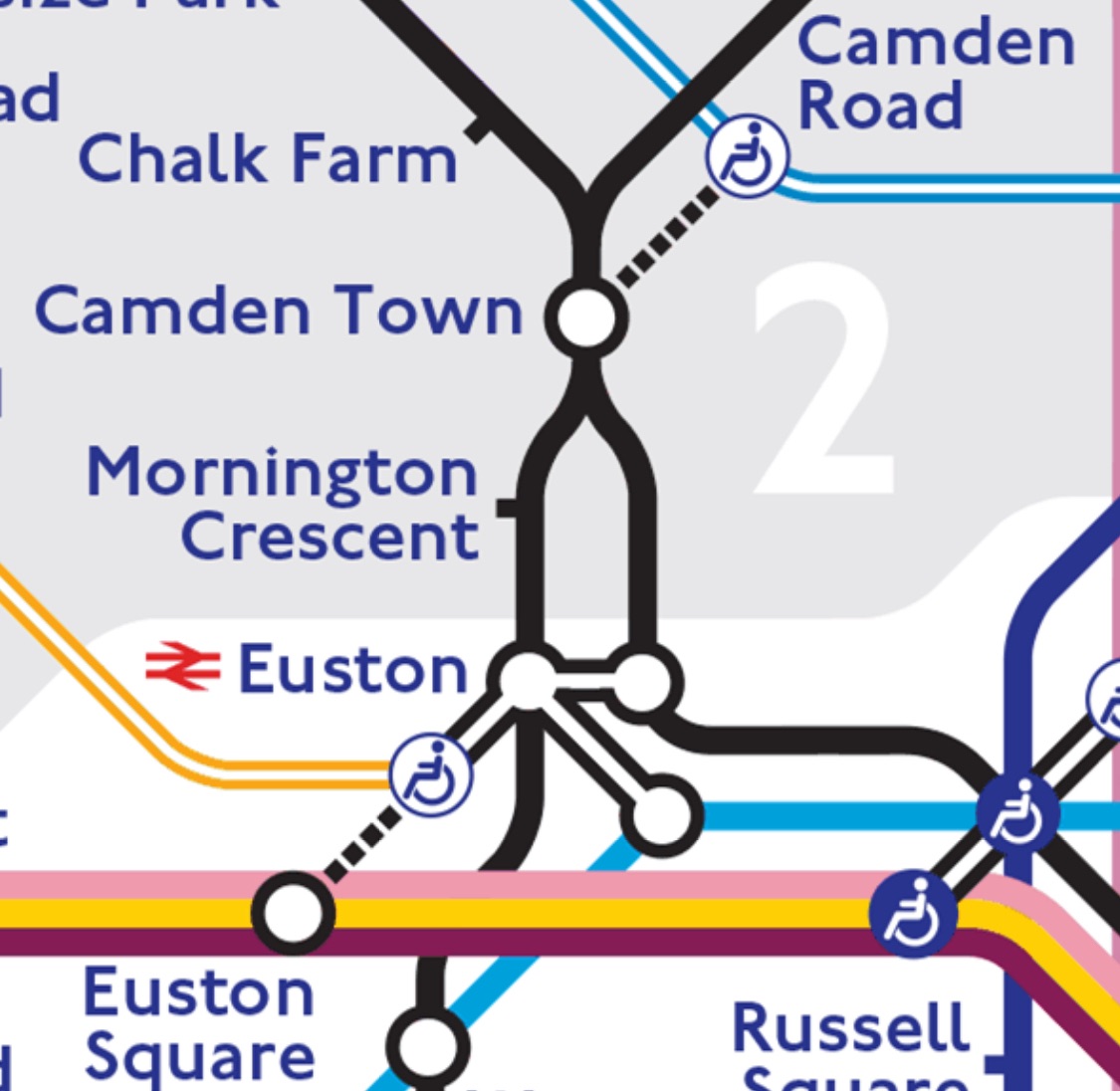

Another line that’s rather confusing is the Northern Line, which has two branches which pass through central London, meet up again between Euston and Camden Town, and then separate again. Now, Transport for London has long planned to split the line in two, but the aforementioned Camden Town station is the sticking point.

What is now the Northern Line was formed from two separate railways. The ‘Bank branch’ was the world’s first successful deep tube line, and was known as the City and South London Railway, first opening in 1890. Meanwhile, the ‘Charing Cross branch’ was formed from the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway between 1907 and 1914. Whilst both reached Euston station, they were completely separate until the 1920s. They collectively became known as the Northern Line in the 1930s, as part of the ambitious Northern Heights plan to take over some suburban rail lines in North London. Alas, only some of the Northern Heights plan ever came to fruition.

Splitting the Northern Line into separate branches has some key advantages. Currently, with trains from both the Bank and Charing Cross branches serving both the Edgware and High Barnet branches, there’s a limit on capacity. At peak times, there are 24 trains per hour on the Northern Line – which is still pretty frequent, especially by the standards of trains that I’m used to up here in the north of England. But having two fully separate lines could allow much more frequent trains – potentially as many as 36 per hour. That would be a 50% capacity increase and make each branch of the Northern Line equal to the Victoria Line in terms of service frequency.

The Camden Town problem

I mentioned that Camden Town tube station would be a sticking point. Along with nearby Euston, and Kennington in the south, it would be one of three stations where passengers would need to change from one branch to the other. Remember, the plan would be to completely separate each branch, so trains heading north from Charing Cross would only go to Edgware, and trains heading north from Bank would only go to High Barnet or Mill Hill East. At the moment, you can get a direct Northern Line train from Charing Cross to High Barnet, if you’re prepared to wait long enough – about 10 of the 24 trains per hour make this journey at peak times. Should the split be implemented, you would have to change at either Euston or Camden Town, but with the benefit of much more frequent trains.

So why is Camden Town a problem? Well, it’s just not big enough for a huge increase in passengers changing trains. Indeed, it’s just not big enough full stop; on Sunday afternoons, the station is typically exit-only (meaning you can’t enter the station from the street) to manage crowds. Transport for London plans to build an additional entrance, and add extra passenger tunnels and more escalators. The plans also include providing lift access, making it completely step free; at present, there’s step-free interchange between the two Northern Line branches, but it’s not possible to enter or exit the station without using steps or an escalator.

The plans to rebuild Camden Town have existed for years, but funding hasn’t been forthcoming.

Also, simply rebuilding Camden Town station will not, in itself, be enough. To operate a more frequent service, London Underground will also need extra trains. There were plans to order additional trains for both the Northern and Jubilee Lines, which operate similar trains built around the same time by the same manufacturer (Alstom). However, the business case was hard to justify at the time. Perhaps new trains could be ordered just for the Jubilee Line, and then the old Jubilee Line trains would operate on the Northern Line?

But what do we call it?

If the split does occur, it would be interesting to see if both new lines get a new name, or whether one remains the Northern Line. And if so, which one? I would argue that the Morden to High Barnet/Mill Hill East line (Bank branch) would be the best to rename, as Morden is actually the most southerly tube station on the network. It seems a bit strange that the most southerly tube station is on the Northern Line.

It could honour the original builders of the line and be called the Southern and City Line. The original train company was the City and South London Railway, but I’ve re-ordered the name to match the other two ‘and City’ lines – the Hammersmith and City, and the Waterloo and City Lines. That might get a little confusing with the Southern railway company, although with rail franchises now being brought back in house, that might not be such an issue.

I also note that one suggested name for the line back in the 1920s was the ‘Tootancamden Line‘, as it passed through both Tooting and Camden but also sounded a but like Tutankhamun. However, whilst there are several Egyptian mummies in the British Museum, Tutankhamun isn’t one of them, and the British Museum is closer to Goodge Street on the Charing Cross branch of the Northern Line. Also, I don’t think we need another reminder of Britain’s colonial past.

Another suggestion could be the Market Line, as the line passes via both Borough and Camden Markets, and the London’s financial centre. That being said, the closest tube station to the London Stock Exchange is St Paul’s on the Central Line. Although to be fair, the newly-named Mildmay Line is not the closest Overground line to the Mildmay Hospital.

Now, I’m not a Londoner – I generally only have the opportunity to visit London once a year – so I’m sure locals could think of some much better names. I quite like the new names for the Overground Lines, and they celebrate ordinary, modern, diverse Londoners. Which is nice since the three most recent new lines, the Victoria, Jubilee and Elizabeth, have all been about royalty. I’d hope that Transport for London would carry on with interesting new names for any newly-split Underground lines.