For my Zigbee devices, I use Zigbee2MQTT and a Sonoff USB Zigbee dongle as my co-ordinator. As I came quite late to the Zigbee party, I didn’t pick up a proprietary Zigbee bridge, but if I had, I wouldn’t use one. Today, I’m going to go through a few reasons why.

Examples of proprietary Zigbee bridges include the Philips Hue Bridge, the Ikea Dirigera Hub and the Tuya Zigbee gateway, but there are others. Here are my reasons why it’s best to go with a more open system, like Zigbee2MQTT or Home Assistant’s Zigbee integration. I’ve previously compared the two.

Having all your devices on one Zigbee network

Zigbee is a mesh network. That means that, as more devices are added, the network actually gets stronger, as each device can communicate with each other. This is especially true with mains powered Zigbee devices like smart plugs and light bulbs. Therefore, if all of your Zigbee devices are on the same network, the connection between each device should be stronger. I’ve included a diagram of my network above, and you can see the multiple mesh connections between devices.

If you have multiple Zigbee bridges – say one for your Hue lights and another for your Ikea smart plugs – you risk causing interference between networks. Furthermore, Zigbee runs on the same 2.4 GHz frequency band as Wi-Fi, Bluetooth and your microwave oven. Having everyone on one network should reduce interference.

Better device support

Some Zigbee bridges are better than others, when it comes to supporting third-party devices. For example, you might be able to add an Ikea Tradfri bulb to a Philips Hue bridge, but possibly not another kind of device. Zigbee2MQTT has, arguably, the best device support and will work with just about any Zigbee device, regardless of manufacturer. You can check the Zigbee Device Compatibility Repository to see which devices work with which platform.

My Zigbee devices are a mixture of Tuya and Ikea, and they co-exist well within Zigbee2MQTT.

Cheaper

Most proprietary Zigbee bridges cost around £60. Meanwhile you can plug a USB Zigbee dongle into a spare PC, or a low-powered Raspberry Pi device that you may already have. The USB dongles typically cost £20-30 each (my Sonoff ZBDongle-E costs £27 at Amazon at present [sponsored link]), and you’ll only need one dongle and one computer rather than multiple bridges.

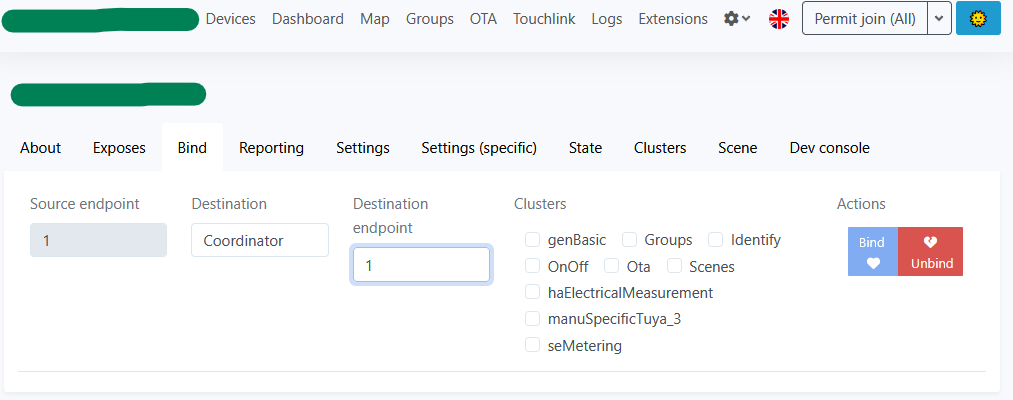

Easier to troubleshoot

With both Home Assistant’s ZHA and Zigbee2MQTT, you can look at the logs to see what’s going on inside your Zigbee network. Hopefully, that’ll help with troubleshooting any devices that aren’t working the way they should. As shown above, you can also get a diagrammatic representation of your network. This lets you see how your devices connect to each other and whether there are any weak spots on your mesh.

Not reliant on cloud services

There’s a risk that your proprietary Zigbee bridges could become expensive paperweights, if their manufacturers decide they’re no longer going to support them and turn off the cloud servers. They may continue to work locally, but if their cloud servers go dark, you may find that you can’t control your devices remotely any-more. By hosting your own Zigbee bridge, you can still have remote access but on your own terms. I use Homeway for remote access to Home Assistant, but you can also set up your own reverse proxy, for example.

Proprietary bridges may offer some convenience and a nice app, But, if you’re willing to put a bit of effort in to manage your Zigbee devices yourself on one single network, I think there are more advantages of going down the route of using Zigbee2MQTT or ZHA.